Lionel Atwill

Lionel Atwill was one of the great horror stars of the 1930s, but his career is too often overshadowed by a sex scandal which brought him to his knees. Alex Hopkins reassesses the life of horror’s most sinister idol.

What is a psychopath? It’s a question which continues to haunt the collective imagination. What leads people to kill – and kill again? Are psychopaths born or made? Barely a month goes by without new articles appearing online examining the traits of a psychopath. Ego mania, a lack of compassion, constant manipulation, a parasitic lifestyle – and, possibly the most insidious characteristic of them all, the one which draws us into the psychopath’s web: superficial charm.

Few actors exemplified this better than Lionel Atwill, the actor who would become a prominent player in the second wave of Universal’s Horror Cycle, moving effortlessly between A and B movies, thrillers, comedies and melodramas. The life of this largely forgotten star of horror is one of tragic proportions. A tumultuous story of a man who reached for the heights before burning out in ignominy in one of the silver screen’s most notorious sex scandals, rejected and demonised – much like the greatest man made monsters of cinema – by the very industry that had spawned him.

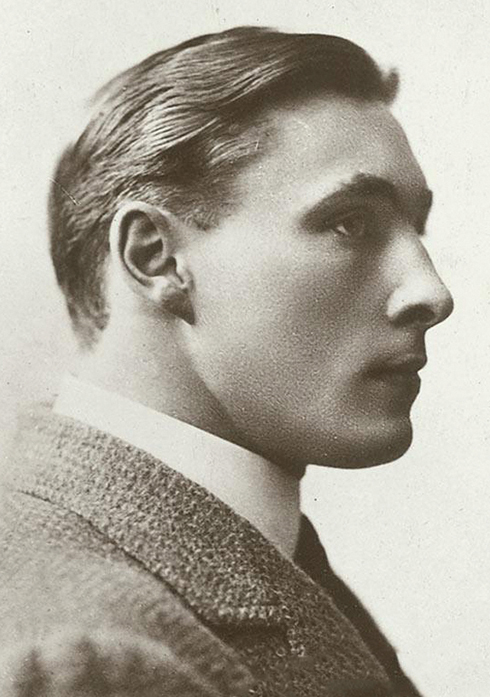

A 1909 publicity still showing a young Lionel Atwill

During the 1930s, when Atwill dominated the screen, the term “psychopath” had gone out of fashion. Instead, doctors had switched to using “sociopath”, thereby focussing on the impact that those exhibiting “moral depravity” had on society. The levels of grandiose behaviour, outward affability and cunning, however, remained the qualities used to classify these potentially lethal individuals.

Atwill’s performance as a deaf mute in 1933’s murder mystery, The Sphinx, is the perfect case study for these types of behaviour, and introduced audiences to the menacing, understated acting that he would repeatedly draw upon throughout his career: the urbane posture and creepy, gleeful rubbing together of his hands; the impeccably timed narrowing of the eyes, followed by the luminous glare of the maniac; the malevolent smile creasing his lips like paper curling up in the dying white heat of a fire, and, of course, the toying with people’s powers of perception as he draws the unsuspecting female beauty into his lair.

Unlike the more obvious monsters created by the likes of Boris Karloff, Lionel Atwill’s contribution to the horror genre was all the more deadly for his uncanny ability to hide his destructive intentions and – most disturbing of all – the enjoyment he derived from his perversions, a pleasure which, we shall see, is given sinister ramifications when we look at the actor’s personal life and catastrophic downfall.

The greatest horror actors are outsiders, and Lionel Atwill was no exception. Born to a wealthy family in Croydon, England, in 1885, he never possessed the looks of a matinee idol, but after studying architecture was nevertheless drawn to the theatre. His debut came at The Garrick Theatre, London, at the age of 20, and he would go on to act in everything from Ibsen to Bernard Shaw. Broadway followed, but he also found the time to gather film credits on the silent screen. Then came the Talkies, and his first feature was 1932’s The Silent Witness. It was in the same year that he would make what is widely regarded as his breakthrough performance, opposite Fay Wray, in Doctor X. As the twisted Doctor Xavier, Atwill would distinguish himself as a rising star in horror, and in 1933’s The Vampire Bat (also starring Wray), he would cement his reputation for evilness as the suave Dr Otto Von Niemann, the first of the many “mad scientists” that he would become most closely associated with.

It’s a typically nuanced Atwill performance: the appealing obsessive, respectable, cordial in public, but in private, conniving and relentless in his pursuit of his Promethean desires. As with so many of Atwill’s 1930s outings, it’s only towards the end of the narrative that we see the catastrophic collision between the doctor’s twisted exterior and interior worlds. But, as always, the hints of wickedness are there from the beginning, from the contemptuous look he gives the village idiot who he revels in framing for the “vampire” murders, to the ever-ready, splayed fingers of his hand, and that ominous, very stilted, hands-behind-back walk which threatens to erupt into leering, outright insanity at any moment.

Atwill as Ivan Igor in Mystery of the Wax Museum (Warner Brothers 1933)

Atwill seemed unstoppable in the 1930s. Mystery of The Wax Museum (1933) followed The Vampire Bat, and saw him cast as the sexual predator, Igor – an almost sympathetic monster in a similar mode to Lon Chaney’s Erik in The Phantom of The Opera (1925) – cruelly disfigured in a fire, but none the less deadly in his pursuit of Fay Wray. His next assignment, in Paramount’s Murders in the Zoo (1933), would feature Atwill’s most warped performance yet, with a profoundly disturbing opening scene in which he is methodically, coolly, yet rigorously sewing together the mouth of a man who has had a dalliance with his wife. Again, Atwill’s Eric Gorman is evidently rejoicing in his sadism, and the film is particularly unsettling in its suggestions of sexual abuse within a marital relationship. From his initial gentlemanly allure, to his portrayal of the calm assassin as he casually throws his wife to the crocodiles, to the wide-eyed panic in the final scenes as he goes into overdrive, Atwill is infinitely compelling.

Inspector Krogh (Lionel Atwill) loses his arm a second time to the Monster (Boris Karloff) as he attempts to save young Peter von Frankenstein (Donnie Dunagan) in Son of Frankenstein (Universal 1939)

The most interesting – and accomplished – actors in horror embrace a variety of work from outside the genre. Atwill painstakingly built his craft by moving sideways into crime capers such as The Solitaire Man (1933) and melodramas like The Devil is a Woman (1935), starring opposite Marlene Dietrich. He’d even work with James Whale in a non-horror picture, the comedic bio-pic of actor David Garrick in The Great Garrick (1937). But he would always return to the genre which was by now bringing him considerable fame and wealth, and it was here, in 1939, that he was to give possibly his most memorable performance, in Son of Frankenstein, Universal’s attempt to breathe fresh life into the infamous horror cycle. As the one-armed Inspector Krogh he is captivating, delivering a performance which is both comedic (who can forget the scene in which he sticks darts into his wooden arm?) and moving, as he relays the confrontation with the monster which caused his disfigurement.

The die was cast: Atwill’s name would become intricately linked with horror, but at the same time he continued to successfully segue into other genres, enjoying himself in comedy-horror The Gorilla (1939) and even the musical comedy The Three Musketeers (1939). His diversity proved to be his greatest strength, but things were all about to change for Lionel Atwill, with a turn of fortune that mirrored the disasters usually reserved for the protagonists he played.

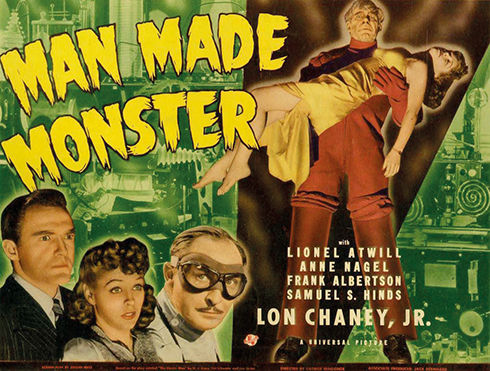

A lobby card poster for Man Made Monster (Universal 1941) in which Atwill plays the evil Dr Rigas

The 1940s began well for Atwill. After being relegated to B picture territory, he was back in A pictures with The Great Profile (1940) and Boom Town (1940), albeit in a small, supporting role. In 1941, he was cast as Dr Paul Rigas in Man Made Monster, back on familiar ground, playing a deranged scientist, a man who boasts of killing animals in his youth, and naturally progresses to inflicting deadly electrical currents on Lon Chaney Junior, in an attempt to create a human machine capable of world domination. The Nazi overtures are there from the beginning: the proud, reckless declaration that he is “mad” and the all-consuming quest to fashion a “master race”. Once again, we see an elated Atwill as he terrorises heroine, June Lawrence (Anne Nagel), before being obliterated by the creature he has created.

You can read the full version of Lionel Atwill’s biography in Classic Monsters of the Movies issue #2, available in the shop now

No one played the sexually lascivious degenerate better than Atwill, but in the early 1940s rumours began circulating about his colourful private life. By this time, Atwill had been married three times: to Phyllis Ralph in 1913 (divorced 1919), actress Elise Mackay in 1920 and socialite Louise Cromwell Brooks (considered one of the most beautiful women in Washington) in 1930. This in itself, was not an issue, but talk of sado-masochism, cross-dressing and group sex hardly ingratiated him with the Hays Office, and neither did statements such as this: “All women love the men they fear. All women kiss the hand that rules them… I do not treat women in such a soft fashion.”

Check out our feature on 1933’s The Vampire Bat in Classic Monsters of the Movies issue #25

Dark words, which would come to haunt him in 1941 when he was questioned about an orgy at his palatial home, which was attended by an underage girl. The ensuing court case transfixed the film community. Here was something they could all have some fun with: the immoral horror hero with the crazed glint in his eye, who, it seemed, could neither control his rapacious sexual desires onscreen or off. Atwill would fall from grace in 1942, when he lied under oath (“like a gentleman,” he claimed, in order to safeguard his friends), and was indicted with perjury. The blow to his career was like the electricity that charged through the veins and floored Dr Paul Rigas. Atwill’s life would never be the same.

Doctor Bohmer (Atwill) schemes with Ygor (Bela Lugosi) in The Ghost of Frankenstein (Universal 1942)

One of the cruellest things about Hollywood is the gratification that the system takes in watching the god like creatures it has manufactured self-destruct. Not since the Fatty Arbuckle scandal of the 1920s had such a prominent celebrity come to such a crushing end. A sex scandal which would raise few eyebrows these days had effectively destroyed the reputation of one of the giants of horror. But like the indefatigable mad men he portrayed, Atwill forged on, and his attempts to revive his career were admirable. In 1942 alone, there were accomplished performances in The Mad Doctor of Market Street, The Ghost of Frankenstein and The Strange Case of Doctor Rx, and between 1943 and 1946 he made 10 films, including 1944’s House of Frankenstein. His last credit for Universal – studio of some of his greatest triumphs – was 1945’s House of Dracula.

In his final years, Atwill’s much troubled personal life improved: in 1944 he would marry for the fourth time, to the much younger Paula Pruter, who would give birth to his only child, Lionel Anthony Atwill, who is now a retired writer. But this happiness was to be short-lived; in February 1946, while shooting the serial Lost City of the Jungle, he became ill with bronchial cancer, and had to be replaced by another actor. His death on 22 April 1946, as with so much of Atwill’s life, was full of tragic irony. Incapacitated amidst the splendour of his Pacific Palisades home, he watched helplessly as his body, the vital instrument which had lent him that terrifyingly elegant, indomitable screen presence, wasted away to nothing. One could argue that he had every right to feel both betrayed and bitter.

But, as with all the greats, he lives on in the flickering light beam of the movie projector. Of the last movies, Fog Island (1945) is perhaps the finest; it is certainly my favourite. Those magnificent Atwillian touches are all there: the evil flamboyance, the eerie stillness, the deranged rocking, the casual smoking of a cigarette and that deliciously debonair manner while he announces someone’s imminent doom. The deadly charm of the narcissist; the callousness and complete lack of remorse of the psychopath. It is surely for these cinematic traits that Lionel Atwill should be remembered – and celebrated.

Warning: Undefined variable $aria_req in /home/lassicmo/public_html/wp-content/themes/classicmonsters2/comments.php on line 8

Warning: Undefined variable $aria_req in /home/lassicmo/public_html/wp-content/themes/classicmonsters2/comments.php on line 13

Thank you for the article. The lives of our long past heroes is truly fascinating.

While I’m sure the scandal was embarrassing, it sounds as if he was working steadily in the same kind of roles he took before the scandal right up until his death.

I understand Arbuckle was cleared of all charges but it wasn’t enough to save most of his career. On the other hand here we have an apparently true case of scandal where the subject was NOT prevented from working steadily. Curious.

“Got something to say?” Aye. All this talk of “sociopaths” and “psychopaths”. They’re medical terms, hardly applicable to working actors making a living as best they can. Atwill, like many others in the Hollywood hills of sunny California, found a niche for himself portraying a certain type of character that the paying audiences came to expect of him, regardless of reality. Therefore he was exploited by the film industry, and can hardly be blamed for his continued employment in the type of part that the studio knew the cinema-going audiences expected to see him in. It seems to me that a large percentage of the audiences of those times possessed a good deal more sophistication than is bestowed on modern commentators and horror film fans. They enjoyed and accepted those films as the tuppenny ha’penny yarns they were. They didn’t take ’em in deadly earnest. The fact that Atwill continued to be employed in the roles that paying customers were accustomed to seeing him in, almost up to the time of his death, is not as “curious” as one commentator seems to think. Arbuckle was implicated, rightly or wrongly, in a scandal that involved the death of a young woman. What did Atwill do? Throw parties at which blue films were shown. The imagination boggles at the modern world(!)

Absolutely fascinating. I love watching these old Universal horror movies. The acting is often over the top, the screenplays are borderline ludicrous, and the cinematography takes you back to a lost place and time… In other words, watching these movies is pure escapist fun!