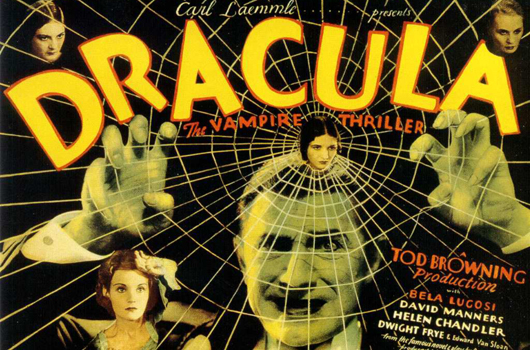

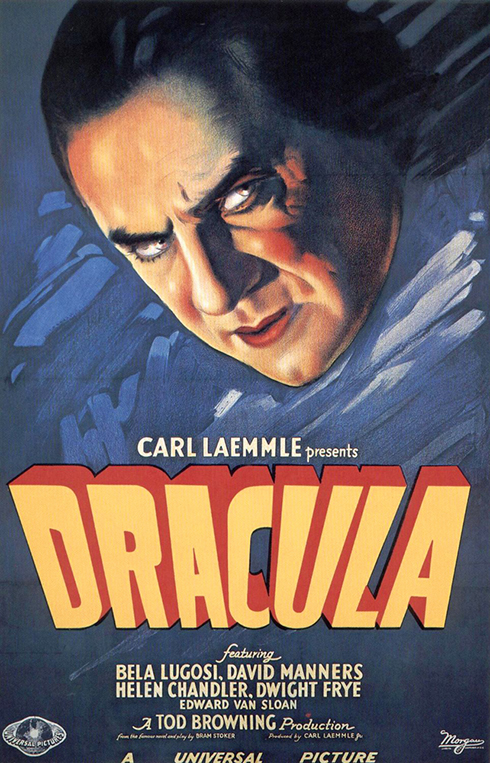

Dracula (Universal 1931)

Dracula Universal 1931 – the film that gave birth to the most iconic image of Dracula the world has ever known, granted a little known Hungarian actor his big break, and marked the beginning of a whole new cinematic genre

The image of Bram Stoker’s Dracula created by Universal Pictures in 1931, played by Bela Lugosi, is, without doubt, the face that many have since attached to that Irish author’s title character. Stoker’s novel was first published in 1897 and, although a giant of English literature today, made little critical impact upon its release, although what scant attention it did receive was favourable. Sadly, it did not really ever become revered until F W Murnau’s 1922 pirated version on film, Nosferatu, long after Stoker’s death. As a result, Dracula did not make much money for its author. In fact, in the last year of his life, he was so poor that he had to petition for a compassionate grant from the Royal Literary Fund, and in 1913 his widow, Florence, was forced to sell his notes and outlines of the novel at a Sotheby’s auction. They were purchased for a little over two pounds.

Despite Murnau swapping London for Bremen and changing character names, Mrs Stoker was not fooled. She sued successfully, and it was ordered that all prints of Nosferatu be destroyed; thankfully, whatever the rights or wrongs of the case, she failed, and we can still delight at this silent masterpiece today. But Nosferatu holds its place in this history for much more; effectively now on the literary map as well as the cinematic one, Dracula was given a contemporary treatment, and developed for the stage by one time friend of Bram Stoker, and fellow Irishman, Hamilton Deane, in 1924.

The Count (Bela Lugosi) takes a keen interest in Renfield’s (Dwight Frye) minor injury in Dracula (Universal 1931)

Deane, originally intending to play the lead himself, ended up taking on the larger role of the vampire hunter Van Helsing, with the part of Dracula going to Raymond Huntley. First presented at Derby’s Grand Theatre in England, Deane’s play was an immense hit, and toured successfully for the next three years, eventually opening at London’s Little Theatre on St Valentine’s Day, 1927. Londoners ignored the harsh panning by the critics and went to see it in their droves, loving such publicity touches as a trained nurse being in attendance at each performance in case the weak-hearted should succumb. American producer Horace Liveright had his eye on developments, and ultimately bought it for Broadway, engaging John L Balderston to simplify and yet further update the slightly plodding plot.

Casting the lead for Dracula Universal 1931

The lead went to 44 year old Bela Lugosi, a one-time matinee idol in his native Hungary, but now a political refugee and jobbing actor in America. Lugosi would, not for the last time, be pitted against his nemesis in the guise of the actor Edward van Sloan, looking twenty years Lugosi’s senior but in fact being twelve days younger. Dracula was a Broadway hit, and played for 261 performances, eventually closing in New York in May of 1928 before embarking on a tour.

Dr Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) proves that he has discovered the Count’s (Bela Lugosi) secret in Dracula (Universal 1931)

All through this, Universal Pictures had been keeping its eye on the property, but were wary of the difficulties in telling the story as a silent motion picture, and also of running into problems with the censor. However, with the imminent advent of the talkies, and a relaxing of censorial control, the project seemed suddenly possible. Various adaptations and treatments were solicited from a number of Universal scenarists, but in August 1930 the studio paid $40,000 for the rights to both book and play, and within a month a script was completed by Dudley Murphy, with a little belated help in the guise of a few final flourishes provided by Garrett Fort. It was Fort, however, who received full screen credit.

Choosing Dracula Universal 1931’s director

Established stalwart Tod Browning was drafted in to direct and, of course, Universal were not willing to cast a virtually unknown Lugosi in the film, earmarking it for the Man of a Thousand Faces himself, Lon Chaney. Undoubtedly, however unsuited to the role he may have been in reality, Chaney would have made Dracula completely bankable, but despite being offered a three picture deal by Universal in order to tempt him, the star, always insecure about money, decided to sign on with MGM for another five years. Any further negotiations were thwarted as Chaney developed pernicious anaemia following a routine tonsillectomy, the wound in his throat refusing to heal properly. Chaney did make a talkie in 1930, a recreation of his silent classic The Unholy Three, but two weeks before its debut, on 23rd June, the actor was diagnosed with lung cancer. He retreated to his mountain cabin to rest, but died alone at age 47 in St Vincent’s Hospital.

After considering both Conrad Veidt and a very young John Carradine as replacements, Universal brought Lugosi in for a screen test and he won the role. He was awarded a two-picture deal at $500 per week, despite still speaking very little English. He learned his lines phonetically “like the words of a song”, and with his uncanny leer and exotic, mid-European lilt, went on to deliver his definitive performance. Dracula was allotted an A-picture budget of $355,050, and on a studio backlot set of a country inn, cinematographer Karl Freund’s cameras started rolling on 29th September, 1931.

Dracula Universal 1931 – filming schedule

The film shot in just 42 working days, wrapping in mid November, with a Spanish version, starring Carlos Villarias (billed as Carlos Villar) as the Count, shooting on the same sets at night. Aimed at the foreign-language markets, this alternative edition was directed by George Melford, and is considered by many to be an improvement on its English language counterpart. It, without doubt, benefits from a brisker pace, but some would argue that Browning’s brooding sets and malevolent atmosphere have stood the test of time better. However opinions vary, there can be little doubt that the cast and crews of these foreign night shoots – literally, foreigners – generally had the advantage of seeing the previous day’s rushes, and so could improve upon camera angles, style and delivery. The Spanish version also runs for an extra 19 minutes, giving it time to expand the plot a little, which somehow makes it more satisfying. But although critics these days are quick to judge the Browning version harshly, we must remember that it is now over 80 years old and, despite its many weaknesses, held audiences easily in its thrall in 1931. When Realart re-released it in a double bill alongside James Whale’s Frankenstein in 1936, the shortening by a further 10 minutes to a brisk hour and a quarter didn’t help its continuity, yet still the people flocked. We must also remember that, without Dracula’s initial success, the whole Universal horror era would simply not have happened; something, at least, to be grateful for.

Renfield (Dwight Frye) proves a key to understanding the plans of the vampire for Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) in Dracula (Universal 1931)

Criticised in the main for excessive dialogue and plodding direction, Browning’s Dracula suffers for his inexplicable but ardent desire to behave as if the vehicle were still a play. His long and medium shots act almost as if the audience were viewing the action on a stage, and, despite cinematic freedom, he even refrains from filming the scenes which take place offstage in the play due to technical considerations, but could have worked so well on the screen. For example, Dracula’s flight in wolf form from the Seward home, Renfield (Dwight Frye) commanding his army of rats and Mina’s (Helen Chandler) midnight liaison with vampire Lucy (Frances Dade), are all missed opportunities, simply referred to in dialogue after they’ve occurred, hampering the overall flow even further.

The Count (Bela Lugosi) has plans for Mina Seward (Helen Chandler) in Dracula (Universal 1931)

The scene on board the England bound Vesta, in which Dracula, summoned forth by a crazed Renfield, sees off each crew member one by one, and could have added real horror and drama to the proceedings, was never filmed despite being scripted. It’s also a pity that the film’s climax, where the Vampire Count is hunted down to his lair at Carfax Abbey to be staked through the heart, also takes place off screen, being represented by a cry from Lugosi which is hardly bloodcurdling. Even bearing in mind the likely reaction of the early 1930s censors, one can’t help but feel that Browning simply opted out, sacrificing some of the story’s powerful potential. But the scenes that redeem it, namely those opening masterpieces in Transylvania, and the dramatic murdering by Dracula of Renfield at Carfax, in the mistaken belief that the lunatic has betrayed him, are enough to spur on the film’s diehard fans in its perpetual defence. Surely any film which can define a character so vehemently in the eyes of the world deserves its place among the greats.

Dracula Universal 1931 was written by Nige Burton

It is a slightly flawed masterpiece. It’s obvious adaptation from the stage makes it slightly “stagey” but in all else it is mesmerising.

There’s an eerie spookiness that permeates the film, helped in part by the lack of a music score. Sound effects of a racing coach, creaking doors, slamming coffin lids and scurrying vermin are made all the more creepy when punctuating the dead silence. I never find the so-called staginess a hindrance; on the contrary, it serves that overall feeling of dread. One is always wary of Dracula even when he is offscreen, such is the power of Bela Lugosi’s iconic performance.