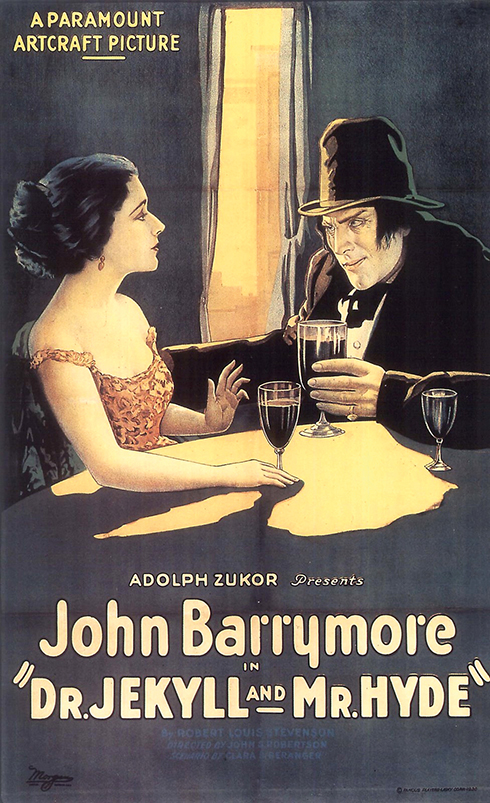

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Paramount 1920)

There have been many adaptations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella ‘Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ for both stage and screen, but few leave the lasting impression of Paramount’s 1920 silent version, boasting in its dual lead role the crown prince of Broadway’s royalty, handsome John Barrymore.

Often overlooked, the earlier rendition is truly the stuff of nightmares, with Barrymore’s fiendish Hyde the archetypal monster from under your bed. Prowling Dickensian Soho, this drooling, ancient arachnid scurries along, barely balancing on spindly spider legs, desperate to discover the exhilaration of being able “to yield to every evil impulse – yet leave the soul untouched!”

A tender moment between Millicent Carew (Martha Mansfield) and Jekyll (John Barrymore) in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Paramount 1920)

Barrymore was a leading light in the Hollywood glitterati, and would rise to dizzy heights of fame and fortune before sensationally crashing and burning, leaving behind one of the most poignant of Tinseltown’s tragic tales as his legacy. Still in his prime in 1920, he imbues his kindly Dr Jekyll with all the tropes Stevenson intended, while creating in Hyde a creature so manifestly ugly in countenance that he out-creeps any of the earlier or later simian-inspired alter egos.

The Scottish author’s short story is presented as more of a mystery, with the action devoid of any love interest. A year after its publication, American writer Thomas Russell Sullivan set about adapting it for the stage, but realised he would have to introduce some romance and a little bawdiness if it were to appeal to Victorian theatregoers. Hence we get our two familiar female leads, one each to counterbalance the good Jekyll and baser Hyde.

Sullivan’s play gives us the saintly Jekyll of independent means, a young man whose altruism knows no bounds. Bound socially to the hedonistic Sir George Carew (Brandon Hurst), he has too won the heart of that unworthy’s daughter Millicent (Martha Mansfield).

Dr Lanyon (Charles Lane) does not subscribe to some of Jekyll’s (John Barrymore) wilder theories in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Paramount 1920)

It is at this point that scenarist Clara Beranger departs from both book and play and takes us straight into the world of Oscar Wilde, developing Carew as a Henry Wotton type character hellbent on proving that Jekyll could not possibly “be as good as he looks,” as he relentlessly tries to corrupt the young doctor.

Taking Jekyll to ‘one of London’s music halls’, the depraved Carew throws sultry singer Miss Gina (Nita Naldi) into his arms, but the good physician manages to resist temptation and leaves the venue with his friend Richard Lanyon (Charles Lane). Once home, the bewildered doctor extols to his companion the delights of being able to separate the good and evil of man’s soul, allowing it to be “housed in different bodies.” A vaguely disturbed Lanyon leaves, but Jekyll is determined and – naturally – succeeds.

The first transformation is as powerful as it is technically adept, taking a leaf out of the book of Richard Mansfield’s acclaimed stage metamorphosis. A writhing, twisting Barrymore accomplished the primary stages of his shift into Hyde purely with facial contortions before a cut to Jekyll’s hands dissolving into talon-like spidery claws. As we cut back to a headshot, we come face to face with pure evil, the chisel-featured monster’s lank hair hanging languid from a pointed dome of a cranium.

Liberated, the fiend makes a beeline for Gina, but soon tires of her. He throws her out into the night while he pursues his pleasures in London’s corrupt underbelly, but not before he has procured from her an Italian poison ring, and carries on his nefarious lifestyle under the protection of Jekyll. However, when his brutality boils over into the trampling of a small boy, a compensation payment is proffered in the form of a cheque drawn on Jekyll’s bank, leading Carew to suspect the doctor’s involvement. Confronting him in his lab, he tells Jekyll that unless he can explain his connection to “a vile thing like Hyde,” he will be forced to withdraw his consent for the forthcoming marriage to Millicent.

Hyde (John Barrymore) does not react well to Carew’s (Brandon Hurst) withdrawal of his daughter’s hand in marriage in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Paramount 1920)

Enraged, Jekyll reverts to Hyde and violently murders Carew in a scene which, glimpsed in its authentic blue tint and projected at the correct speed of 18 frames per second, is as chilling as anything F W Murnau’s Nosferatu could offer a couple of years later. Few early cinematic images are as chillingly stark as the unwary Jekyll, slumbering in his bed while a huge, ghostlike spider crawls onto his blankets and dissolves into him; he wakes as Hyde.

A mortified Millicent is summoned, and Henry – now feeling a little more like himself again – promises to do everything in his power to track down Hyde. But the stronger personality once more gets the better of the weaker, and as Hyde takes control again, he lets a despondent Millicent into the lab, but the terrified girl flees in terror. Friend Lanyon comes in to see what all the fuss is about just as Hyde expires, having taken some poison hidden in the ring, before reverting to Jekyll. The girl comes back and, although Lanyon realises the truth, he explains that Hyde murdered Jekyll to preserve the poor damsel’s nerves as well as his friend’s reputation; Millicent crouches moribund by the lifeless body of her fiancé.

Running for a feature length hour and nineteen minutes, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a tour-de-force of silent cinema, and could arguably be considered the first American horror film proper, even though it’s commonly accepted that particular crown usually goes to Universal’s 1931 production of Dracula. We have all the usual trappings of pre-sound movies in that much of the dialogue is implied, with only the absolutely necessary snippets being furnished via the elaborate title cards, and the acting is grossly over-the-top in places, a feat deemed necessary back in the day to communicate emotions and plot details. But these, as in any other silent masterpiece, must be overlooked to evaluate a film effectively on a much more subtle twenty-first century calibration. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a fine film, with above average performances in general, iced to perfection with that powerhouse of a portrayal by John Barrymore.

You can read this article in full in Classic Monsters of the Movies issue #11:

As the minxishly naughty Sir George Carew, Brandon Hurst sparkles away delightfully, exploiting the fallible Jekyll with relish before getting his comeuppance for such a malignant sport. The London born actor would resurface in a couple of other horror pictures before the decade was out, playing the treacherous Jehan opposite Lon Chaney’s Quasimodo in 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and jester Barkilphedro in The Man Who Laughs (1928).

The virtuous but lovelorn Millicent – a role turned down by Tallulah Bankhead – went to Martha Mansfield, who gives a subtle and understated performance balancing perfectly with Barrymore’s distracted and disinterested Jekyll. This unassuming beauty was all set for a promising career when she was signed by Fox in 1923 to play Agatha Warren in The Warrens of Virginia (1924), but as shooting was about to wrap she was returning to her car after completing a scene when her dress caught fire from a carelessly discarded match. Her co-star Wilfred Lytell sprang into action and doused the flames with his coat, but the actress died in hospital the next day from her severe burns; she was just 24 years of age.

As Millicent’s underworld oppo Gina, former Ziegfeld Folly Nita Naldi excels, bringing a showgirl worldliness tempered with a fresh vulnerability to Hyde’s unfortunate concubine. Born Mary Nonna Dooley to Irish-American parents in New York, she would soon be starring opposite Rudolph Valentino in 1922’s Blood and Sand, after which she would act in Hollywood until 1926, when she eloped to Paris with J Searle Barclay, whom she had been dating for six years. The union failed in 1931, and a dejected Naldi returned to New York and filed for bankruptcy. She had made three further films in Europe, but an attempt at a 1940s career revival was unsuccessful, although she did work on stage, and later television, before dying of a heart attack in her room at the Wentworth Hotel in 1961.

Playing the music hall proprietor was Lionel Barrymore protégé Louis Wolheim, who had suffered a broken nose whilst playing football at Cornell University in his youth. The Jewish-American actor had spent years struggling when Barrymore discovered him and told him his face could be his fortune. The star introduced Wolheim to the New York theatrical scene, and he went on to make a number of appearances in film, most famously as Kat in Lew Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930).

Directed by John S Robertson and produced by Jesse L Lasky, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was released by Paramount to great effect and garnered excellent reviews for both Barrymore and Robertson – an enduring example of fine art on film.

Leave a comment