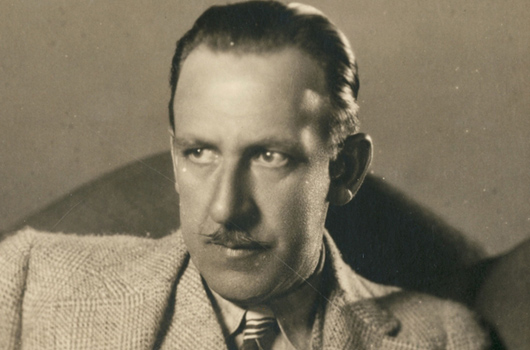

Tod Browning

Tod Browning was born Charles Albert “Tod” Browning in Louisville, Kentucky on 12th July, 1880, the second son of Charles Albert and Lydia Browning.

As a young boy, he would frequently stage plays in his backyard, and developed a keen fascination for the theatre and, in particular, circus performers. Infatuated with a sideshow dancer, and spurning his well-to-do family, Browning ran away at the age of 16, making a life for himself in various circus and carnival troupes, eventually working as a talker for the Wild Man of Borneo, and performing a live burial act as “The Living Corpse”, before becoming a clown with the Ringling Brothers Circus. These many and varied experiences as a young man would inform much of Browning’s later film work.

Performing in Vaudeville as an actor, magician and dancer, Browning graduated to director of a New York variety theatre, where he crossed paths with D W Griffith who, coincidentally, was also from Louisville. The meeting proved propitious to Tod Browning’s career in movies, and he went on, alongside the comedian Charles Murray, to star in one-reeler nickleodeon comedies for Griffith and the Biograph Company.

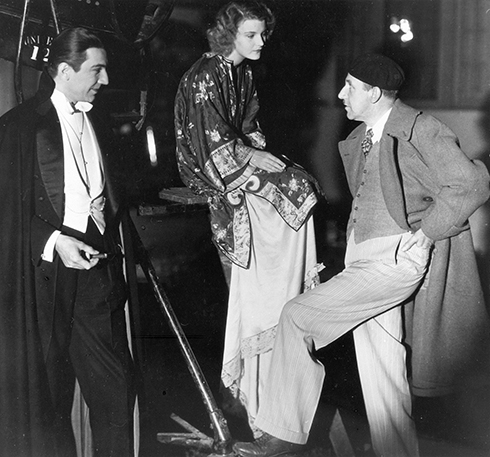

Bela Lugosi and Helen Chandler chat to director Tod Browning between takes on Dracula (Universal 1931)

Griffith moved to California and began working with Reliance-Majestic studios, and Browning followed, continuing their collaboration as well as finding his own feet as a director, eventually working on 11 shorts for the company during his time with them. The prolific star acted in around fifty films between 1913 and 1919, including a stint in the epic Intolerance, but a fatal car crash in 1915, in which Browning drunkenly drove his car at full speed into a moving train, would interrupt his career and set it in a different direction, the two years it took for him to convalesce and recover from his serious injuries allowing the actor time to develop his script writing skills. Of his fellow film actor passengers, George Siegmann was also gravely injured, while Elmer Booth was killed outright, a fact for which his sister, the later MGM editor Margaret Booth, held a lifelong grudge against Browning.

Check out our biography of Tod Browning in Classic Monsters of the Movies issue #13

For his feature film debut, Browning cut his teeth on a fervid romp about a riverboat captain who sacrifices his life to save his passengers from a consuming fire. Jim Bludso (1917) was a worthy piece, and one which audiences received well.

Moving on to direct for Metro Studios, where he made a couple of pictures with Mabel Taliaferro, Browning left them in 1918 in favour of Bluebird Productions, a subsidiary of Universal Pictures, where he met Irving Thalberg. It was this meeting which would lead onto Browning working with Lon Chaney, and the pair collaborated on The Wicked Darling (1919), in which Chaney played a thief who forces a poor girl from the slums into a miserable existence of crime, and possibly prostitution. The duo would go on to work together on no less than ten films over the next decade.

Tragedy struck again when Browning’s father died, an event which derailed the director’s emotions, plunging him deep into depression and the grip of alcoholism. Being dumped by both Universal and his wife, Alice, proved enough to rally his spirit however and, quitting the booze and reconciling with his wife, he got a one-picture contract with Goldwyn Pictures, producing the moderately successful The Day of Faith, which proved sufficient to restart his career.

Tod Browning relaxes on set with some of the cast of Freaks (MGM 1932)

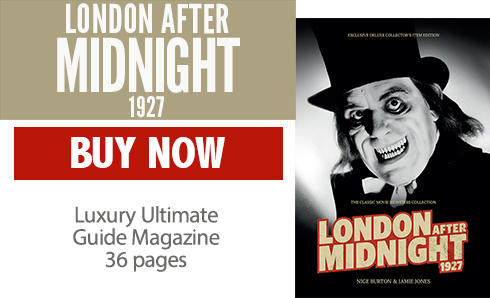

Thalberg reunited Browning and Chaney for The Unholy Three (1925), which tells the woeful tale of three circus performers who devise a scheme to con and steal expensive jewels from rich people by employing elaborate disguises. It is in this vehicle that Browning’s sympathy with the protagonists of his circus background shines through, manifesting itself in the thoughtful way he portrays the film’s antiheroes, making The Unholy Three a resounding success, leading on to a whole series of strong and popular collaborations, including The Blackbird and The Road to Mandaley. Further highlights were The Unknown (1927), which features a young Joan Crawford as the scantily clad carnival girl over whom Chaney’s armless knife-thrower obsesses (a film which many regard as a precursor to Freaks) and Browning’s first foray into the theme of vampirism, the classic but hopelessly lost London After Midnight (1927).

The pair’s final alliance was Where East is East (1929), after which they moved independently on to their first talkies. Tragically, Chaney’s – a superb remake of The Unholy Three (1930) – would be his last too, with the star dying from lung cancer just two months after its release. For Browning, it was The Thirteenth Chair, which was dually released as a silent, and starred the relatively unknown Hungarian actor, Bela Lugosi.

Following Chaney’s death, Universal rehired Browning to direct Dracula (1931) with Lugosi in the title role. Browning had originally wanted an unknown European actor to take the part, and to have him mostly offscreen as a “sinister presence”, but the need for a simpler approach and tangible lead were paramount, and Browning eventually acquiesced. Although eventually achieving cult and classic status, the 1931 Dracula was a disappointment to the studio at the time, and didn’t garner Browning many friends.

After working on the boxing melodrama Iron Man, also made in 1931, Browning began work on the film for which he is possibly most notorious. Based on the short story Spurs, by The Unholy Three’s screen writer Tod Robbins, Freaks (1932) is a dark and nightmarish tale of a love triangle, circus freaks, murder and bitter revenge. Using real sideshow freaks, the film was highly controversial at the time and, despite the cutting of some twenty minutes, was a commercial failure in the States and banned outright in England for thirty years. To many, however, it remains Tod Browning’s finest hour.

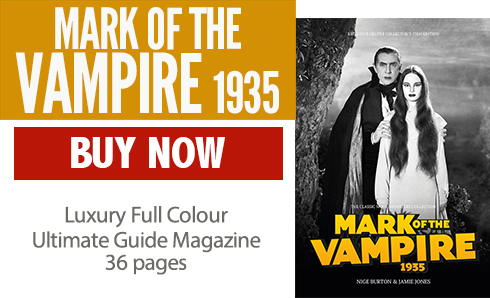

With his career in free-fall once again, Browning struggled to get the go ahead for his requested projects. After working with fellow pariah John Gilbert on the 1933 production of Fast Workers, he was eventually assigned the remake of London After Midnight, 1935’s Mark of the Vampire, with Chaney’s dual roles now split between Lionel Barrymore and Bela Lugosi, the latter essentially reprising his Dracula role, albeit pretend.

But Browning’s taut direction and melancholy pace for The Devil Doll (1936) makes this often overlooked classic a masterpiece, although one which came too late. His final film was the murder mystery Miracles for Sale (1939), after which he announced his retirement, saying: “When I quit a thing, I quit. I wouldn’t walk across the street now to see a movie!” He did do some screenwriting for MGM after this, but repaired to Malibu in 1942, where he slipped into obscurity.

Browning’s wife died in 1944, and Variety mistakenly printed his obituary, due probably to the fact that even close neighbours rarely, if ever, saw him. In the late 1950s, he developed throat cancer, and underwent surgery on his tongue. He never really recovered in spirit and, when his brother, Avery, died in 1959, reportedly attended the funeral from a private room, refusing to be seen by anyone, including family members.

As the original Universal productions of Dracula and Frankenstein found new audiences through television, it is said Browning acquired a set and would watch until the early hours of the morning. It was on the morning of October 6th, 1962, that Tod Browning’s body was found in the bathroom of some friends who had taken him in. He was 82 years of age.

Ironically, just one year later, a screening of Freaks at the Venice Film Festival spurred a massively renewed interest in the man and his unique career. It would have been a fitting final flourish for him, but the fates had other ideas, and he died believing he was forgotten, a relic of some foregone time, and no longer relevant in that much changed world.

Warning: Undefined variable $aria_req in /home/lassicmo/public_html/wp-content/themes/classicmonsters2/comments.php on line 8

Warning: Undefined variable $aria_req in /home/lassicmo/public_html/wp-content/themes/classicmonsters2/comments.php on line 13

Leave a comment