Devil Doll, The (MGM 1936)

The Devil Doll, released on the 10th of July, 1936, was both MGM’s and Tod Browning’s last horror film and, as such, was a superb swansong.

The film features an exquisite performance from Lionel Barrymore as Devil’s Island escapee Paul Lavond. Dragged up as Madame Mandelip, the proprietress of a Montmartre dolly shop, Lavond uses eccentric scientists Marcel and Malita’s six inch humans to exact revenge on those who framed him.

Pernicious and pint-sized: Lionel Barrymore as Paul Lavond as Madame Mandelip proudly displays her demonic dollies in The Devil Doll (MGM 1936)

The resulting cinema is pure Chaney; grotesquely beautiful and a rich study of human foibles. Browning had learned from his faux bloodsuckers of Mark of the Vampire (1935) – the premise of The Devil Doll is fantastic, but at the same time carried beautifully by a finely-tuned, adult script and wondrous special effects.

Dogged determination: Malita (Rafaela Ottiano) experiments on a miniature dog in The Devil Doll (MGM 1936)

To see Grace Ford as little Lachna, nimbly cavorting across giant furniture to throw stolen pearls to a waiting Barrymore outside the window, is as enchanting today as it was at the time of its release.

By turns richly comic and deeply tragic, The Devil Doll’s melancholy finale set atop Paris’s Eiffel Tower, where Lavond says a last farewell to daughter Lorraine (Maureen O’Sullivan), is still hugely affecting. The sense of ‘what could have been’ is almost palpable, and shows Browning’s directorial skills off in their very best light.

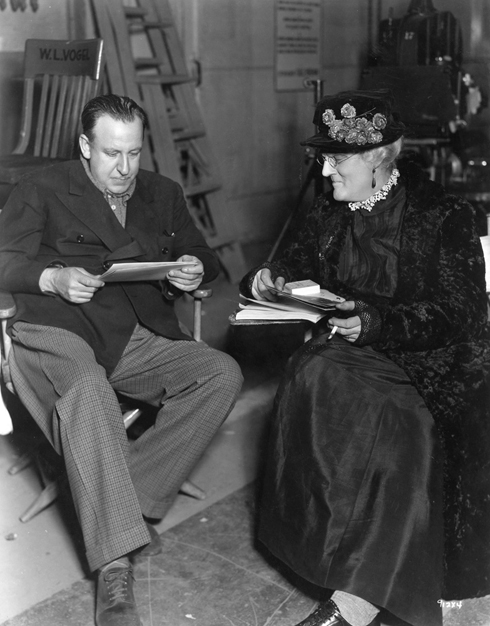

What a drag: Tod Browning and a cross-dressing Lionel Barrymore discuss an upcoming scene in The Devil Doll (MGM 1936)

Based on Abraham Merritt’s novel, Burn Witch Burn, The Devil Doll replaces alchemy with science-fiction in a near faultless script by Guy Endore, Garrett Fort and Erich Von Stroheim.

Police dogs: Madame Mandelip (Lionel Barrymore) discovers that selling devious dollies to the police can be a bit of a drag in The Devil Doll (MGM 1936)

It is a fitting tribute to Browning’s oftentimes chequered career, and a film which never seems to have secured its rightful place among the all-time classics of twentieth century cinema.

Little devils: Original theatrical release poster for The Devil Doll (MGM 1936)

Warning: Undefined variable $aria_req in /home/lassicmo/public_html/wp-content/themes/classicmonsters2/comments.php on line 8

Warning: Undefined variable $aria_req in /home/lassicmo/public_html/wp-content/themes/classicmonsters2/comments.php on line 13

Leave a comment